Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC)

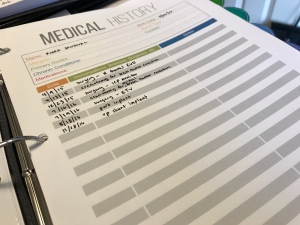

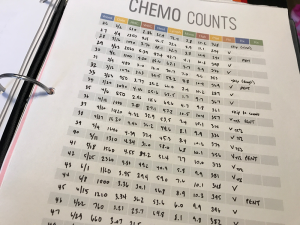

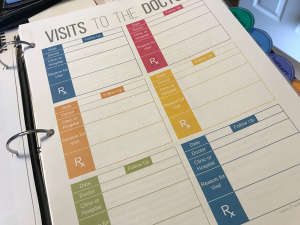

Blood tests are done at every chemo appointment to monitor a patient’s response to treatment. White blood cells fight infection and can be compromised when a patient is receiving chemo. The most important infection-fighting white blood cell is the neutrophil, so doctors look at the absolute neutrophil count (ANC). The ANC is found by multiplying the white blood cell count by the percent of neutrophils in the blood. For instance, if the WBC count is 8,000 and 50% of the WBCs are neutrophils, the ANC is 4,000 (8,000 × 0.50 = 4,000). A healthy person has an ANC between 2,500 and 6,000. When the ANC drops below 1,000 it is called neutropenia. The oncologist will watch the ANC closely because the risk of infection is much higher when the ANC is below 500. Monitoring blood counts allows the medical team to make changes before problems get serious. Keeping track of results lets the oncologist take action early to help prevent many cancer-related problems and cancer treatment side effects. I also keep a log in Kiara’s binder.